A Russian rocket released two Galileo navigation satellites nearly 15,000 miles above Earth early Friday, adding to a growing fleet giving Europe an independent space-based positioning system tracking automobiles, airplanes and cell phone-carrying people around the world.

The identical satellites, nicknamed Alba and Oriana, deployed from their hydrazine-fueled space tug at about 0556 GMT (1:56 a.m. EDT) Friday.

European officials confirmed the rocket injected the phone booth-sized satellites into an on-target orbit about 23,500 kilometers (14,600 miles) up, and declared the mission a total success.

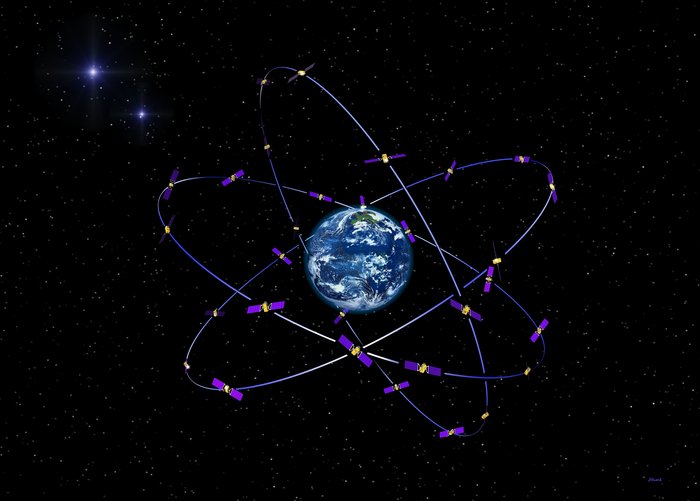

“Tonight, it is a success for Galileo,” said Stephane Israel, chairman and CEO of Arianespace, which operates the Soyuz rocket from French Guiana. “Alba and Oriana are the ninth and 10th Galileo spacecraft to be orbited by Arianespace. They will soon join their teammates in the constellation, which will consist of 30 satellites and build European autonomy in the field of positioning, navigation and timing.”

The 151-foot-tall Soyuz rocket fired away from a launch pad in French Guiana at 0208:10 GMT (10:08:10 p.m. Thursday), soaring through the stratosphere and into space as each of its three core stages took turns accelerating the launcher northeast over the Atlantic Ocean.

The legendary Soyuz rocket, with its roots at the dawn of the Space Age in the 1950s, was flying for the 12th time from the European-run Guiana Space Center on the remote northern shores of South America.

A Fregat upper stage stacked atop the Soyuz rocket took over for a pair of engine firings to guide the Galileo satellites into a circular orbit thousands of miles above Earth. The tandem payloads simultaneously separated from a dispenser on the Fregat stage and radioed their status to Earth as planned, officials said.

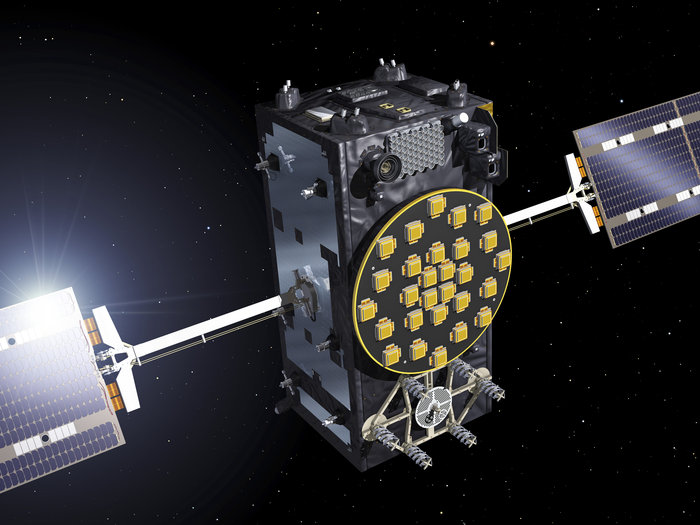

The platforms, each weighing 1,576 pounds (715 kilograms), will extend their power-generating solar panels and slightly lower their orbits to join the Galileo constellation in the coming weeks. The launch targeted an altitude just above the operational fleet to keep from adding space junk to the Galileo traffic lanes.

The Galileo system is Europe’s analog to the U.S. military’s Global Positioning System and Russia’s Glonass navigation satellites, which provide worldwide service. China is building its own global navigation network — called Beidou — while India and Japan are fielding regional versions.

By 2020, European officials say the Galileo system will be fully deployed with 30 satellites — 24 operational birds and six spares — spread in three orbital planes to ensure global coverage.

“We’re not only thinking of Galileo 9 and 10 of the constellation we are now trying to construct, but we also have to think into the future,” said Jan Woerner, ESA’s director general. “There must be a second generation because these satellites will not live forever.

“Galileo is, for me, much more than just some satellites flying around our globe,” Woerner said in remarks early Friday. “It is, for me, the proof for cooperation in Europe and beyond, even in difficult times.”

The satellites launched Friday, made by OHB System of Germany, targeted Plane A of the Galileo constellation. The spacecraft carry L-band navigation payloads built by Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd. of the United Kingdom, which is also responsible for supplying highly-accurate atomic timepieces for the satellites.

Besides offering an independent navigation service, Galileo will give users equipped with new interoperable chipsets extra precision with combined GPS, Glonass and Galileo signals.

Working together, the GPS and Galileo satellites could offer the global population positioning information with an accuracy of just a few centimeters, an improvement from the several-meter error publicly available with GPS today.

The best GPS signals are reserved for military use, just as Galileo’s most accurate positioniong estimates will be regulated.

The Galileo system — expected to cost $7.9 billion (7 billion euros) to complete by 2020 — is run by the European Commission, the EU’s executive body, and the European Space Agency acts as contract agent and technical advisor.

With 10 satellites now in orbit, the Galileo program aims to begin limited services when the 14th craft becomes operational some time next year.

“Ten satellites is only one-third of the full constellation, but we have behind us the full development, and the implementation of the first satellites, so we’re very confident the new ones will be operated with full success,” said Didier Faivre, ESA’s director of navigation.

“We are very confident now with the stage of the production, the state of the tests and the state of preparation in Kourou (at the Guiana Space Center)… We are there,” Faivre said before the launch.

But the initial Galileo satellites have not been spared trouble.

Two spacecraft launched in August 2014 were dispatched into the wrong orbit, but ground controllers maneuvered the satellites into quasi-circular orbits, close enough to their intended positions to be incorporated into the fleet.

Another satellite has a problem with a navigation antenna.

“Many challenges remain ahead, but today we have made another significant step,” said Matthias Petschke, director of the European Commission’s satellite navigation program. “Our objective is that we want Europe to be endowed with the first global civilian navigation satellites. Our objective, in the near future, is to provide new types of services — services for our citizens and for our corporations.”

The next pair of Galileo satellites are set for launch Dec. 17 on another Soyuz flight. They will be shipped from ESA’s test facility in the Netherlands to French Guiana this autumn.

“Galileo will be a powerful navigation system for its worldwide users, and for a variety of applications, and we at OHB are very proud to be able to deliver the core element of this (global) navigation system,” said Andreas Lindenthal, chief operating officer at Bremen, Germany-based OHB.

“The next two satellites are already finished and ready for acceptance, and can be launched,” Lindenthal said. “The other satellites are coming soon in a very tight sequence in the production, assembly and testing activities.”

Officials plan to place four Galileo satellites aboard a heavy-lifting Ariane 5 rocket some time in 2016, which would give the system 16 satellites in space by the end of next year, according to Faivre.

Faivre said the program aims for one Soyuz launch and one Ariane 5 mission — for a total haul of six satellites — in 2017. Another Ariane 5 will go up in 2018 for the Galileo system to fill up with 26 satellites.

The European Commission and ESA plan to order four or six new satellites by the end of the year for launches in 2019 and 2020.