In June 2022, astronauts aboard the International Space Station found themselves in peril. A squall of space debris was hurtling toward them at blinding speeds of 17,000 to 32,000 miles per hour. The crew was able to maneuver to successfully evade the assault. However, it would only be a matter of time before it continued its erratic orbit around the Earth and came around again.

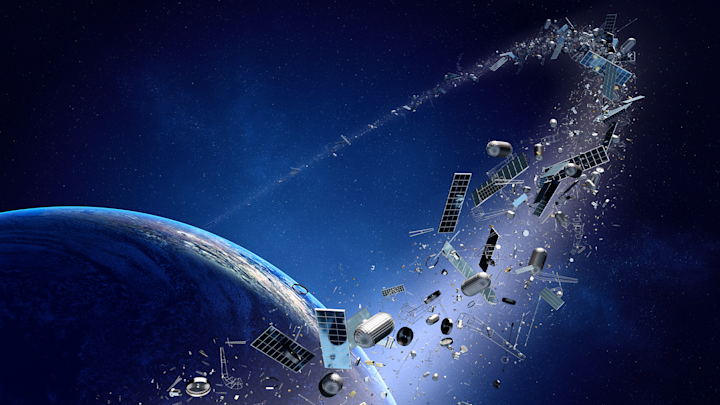

For many, the void of space brings to mind the idea that objects left in space will make their way to the furthest reaches of the solar system– following the trajectory of the Voyager 2 spacecraft, heading to unknown parts of the Universe. But, in reality, the area 220 to 1200 miles above Earth is where thousands of tons of debris from discarded launch rockets, obsolete satellites, and objects unintentionally discarded during space activity find themselves trapped by Earth’s gravitational pull, endlessly spinning in orbit around the planet. The problem is so significant that all space-faring nations track space debris to avoid disastrous collisions.

This space junk has accumulated from the very start of our modern space program, when the Soviets launched the first object in orbit, Sputnik 1, in 1957. Sputnik’s upper stage booster was intentionally discarded into low Earth orbit and remained there until its trajectory dropped, resulting in its burning in the atmosphere. During these last six and a half decades, mankind has launched thousands of crewed and unmanned space flights, an international space station, and over 13,000 satellites into space. Each new mission compounds the problem. Currently, there are over 36,000 objects large enough to track in orbit around the Earth. This space junk, at least four inches in diameter, could easily wipe out a spaceship or satellite. This figure also includes over 1,300 articles larger than a car. But in addition to this, there are approximately a million pieces between .40 inches and four inches, and innumerable smaller fragments. And although these may seem inconsequential, they are not. Debris the size of an aspirin tablet carries the explosive impact of a hand grenade. Even particles the size of rice can act like bullets in space. Although it is difficult to catalog all the estimated 10,000 tons of space debris currently in orbit, some have garnered special attention.

WHAT’S OUT THERE

Spacecraft account for at least 30% of space debris. Today we have over 6,200 operating satellites in orbit and 2,600 non-functional ones. Many of these are still in active orbit as space junk, including dozens of nuclear-powered satellites launched by the U.S. and Soviets in the 1960s and 70s. The oldest defunct satellite still in orbit is the U.S. Vanguard 1, launched in 1958, five months after the Sputnik 1. It sent its last signal in May 1964 but is expected to remain circling the globe for another 170 years. These craft represent a serious threat, in 1996, the space shuttle Endeavor had to fire up its steering thrusters to conduct an emergency maneuver to avoid a 350-pound abandoned air force satellite designed to track ballistic missiles. And in February 2009, the decommissioned Russian satellite the Cosmos 2251 and the operational U.S. satellite the Iridium 33 collided in space. The speed of the impact pulverized both satellites, resulting in a massive cloud of debris.

Since the start of the space program, there have been over 6,200 rocket launches. Rocket boosters account for up to 17% of space junk. Spent rocket stages are among the most dangerous pieces of space debris. Many still have propellant on board and continue to circle the Earth like ticking time bombs. In 1986, a European Ariane booster, which was used to launch a French satellite into space just nine months earlier, exploded, throwing hundreds of fragments into orbit. In the 1970s and early 1980s, seven U.S. Delta booster rockets suddenly blew up in space.

Other mission-related objects such as ejected covers and shields, hardware, electric circuitry, solidified liquids including fuel and sewage, and other devices accompanying payloads comprise about 13% of the debris. In 2009, the crew of the International Space Station had to take shelter in an escape vehicle after a near collision with an old motor that was once part of the ISS. Other known items that may still be hurtling through space include a camera lost by astronaut Sunita Williams during a space walk in 2006, a screwdriver dropped by a cosmonaut working on the Mir Space Station, and the thermal glove that floated out of Gemini 4 in 1965.

The principal source of space debris is the breakup of rocket boosters and satellites in space, which account for 40% of orbital trash. There have been over 500 known breakups. The debris cloud that the International Space Station recently dodged came from a Russian anti-satellite weapon test conducted in November 2021. This targeted blast of a defunct 80s-era Russian Cosmos 1408 intelligence satellite resulted in the formation of two distinct clouds with an estimated 1,500 trackable fragments. These clouds created havoc for the ISS and also hundreds of Starlink satellites, which had to maneuver out of its path.

There have been multiple detonations of defunct space hardware by Russian anti-satellite weapons. Additionally, hundreds of trackable debris fragments resulted from the Star Wars weapon testing conducted in the 1980s. However, the largest deliberately created debris field was from an anti-satellite weapon test conducted by China in 2007. The incident is estimated to have created 23,000 golf-ball size pieces of debris as well as millions of smaller fragments.

Many collisions in space have been due to these untracked fragments. In 1983, on its seventh mission to the ISS, the space shuttle Challenger returned to Earth with a 3 mm chip on the window. Later chemical analysis revealed it to be caused by a speck of white paint approximately 2/10th of a millimeter in diameter. And in 2021, a fragment a few millimeters in size, knocked a hole into the thermal envelope of a robotic arm on the ISS.

There are also various miscellaneous items flying through space, including metal space needles put into orbit by the U.S. Air Force in the 1960s. A payload of over 1.2 billion needles were launched into space by the military to see if radar signals could be bounced off them and return to Earth. The experiment was unsuccessful and swarms of these needles were later suspected in the 1975 breakup of the PAGEOS balloon satellite built to provide a tracking target for geodetic purposes.

CLEANING UP THE MESS As we enter a new age of privatized space ventures, numerous companies have filed plans to launch a combined 14,000 satellites in the coming years. The conversation has veered from the danger associated with the launch into orbit, to the peril of space debris. In 1978, leading NASA scientist Donald Kessler already saw the writing on the wall. He theorized that as space junk in orbit accumulated, a sufficiently large collision of objects in space could lead to a cascading effect of fragments colliding, creating more debris, thus leading to further collisions. This would inevitably create an impenetrable layer of debris that would make terrestrial space launches impossible.

The threat of the Kessler Syndrome NASA fears led to changes in the U.S. Space Program, including modifications to the upper stage rockets to reduce the chance of an explosion in space. Other space-faring nations followed suit, and space debris guidelines, including diverting inoperable satellites to a “graveyard orbit” or de-orbiting and allowing them to burn in the atmosphere, were set in 1993 and adopted by the UN. However, space companies do not always follow the recommendations.

Many scientists believe we are on the verge of meeting the fate proposed by Kessler, unless immediate action is taken to remove material from orbit. Concepts currently in the works range from laser beams to pulverize debris, a space tow truck, a fleet of giant vacuum cleaners, a massive net to envelope and drag debris to a lower orbit, an omni-magnet to capture space debris, and even giant aerogel blobs to absorb fragments. Someday soon, we may see an entire industry built around the removal of the space junk piling up in Earth’s backyard.

The AlienCon Newsletter Team is made up of researchers, authors, and experts in their fields. Join us twice a month as we bring you the latest news, discoveries, and information on all things otherworldly.

Source Credit: https://www.thealiencon.com/newsletter-archives/the-intergalactic-world-of-space-junk/?cmpid=email-aliencon-newsletter-2022-0830-08302022&om_rid=